Economic Policy

Provide Financial Support for Black Workers

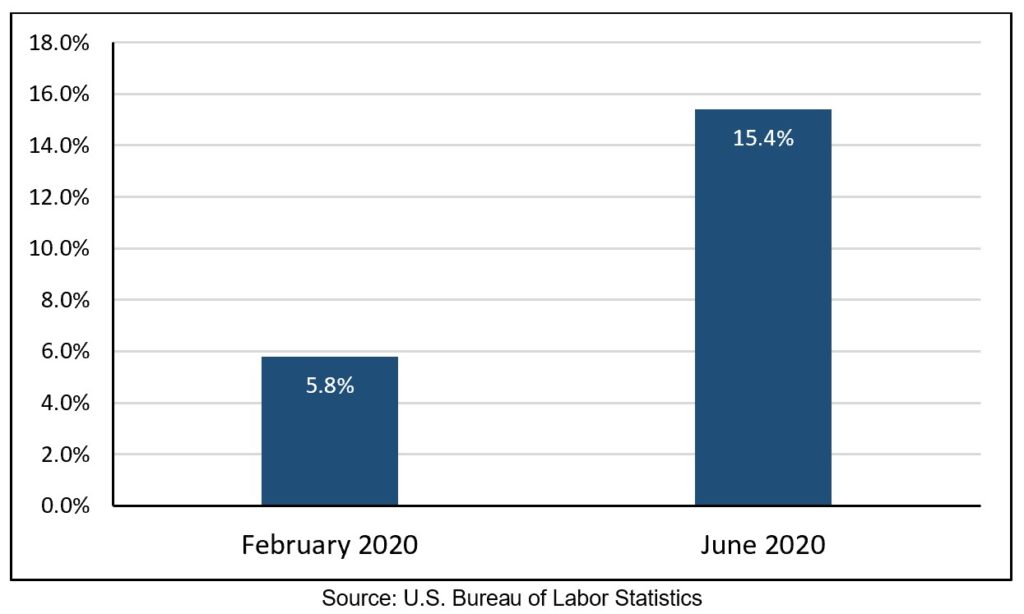

Black workers are over-represented in public transit, childcare and social services, health care, trucking, warehouse, and postal service, and many other frontline occupations deemed “essential.”1 Despite this work, Black communities have experienced high rates of both job and income loss. In June 2020, 15.4% of Black workers were looking for but unable to find work.2

Unemployment Rates for Black Workers Spiked During the Pandemic

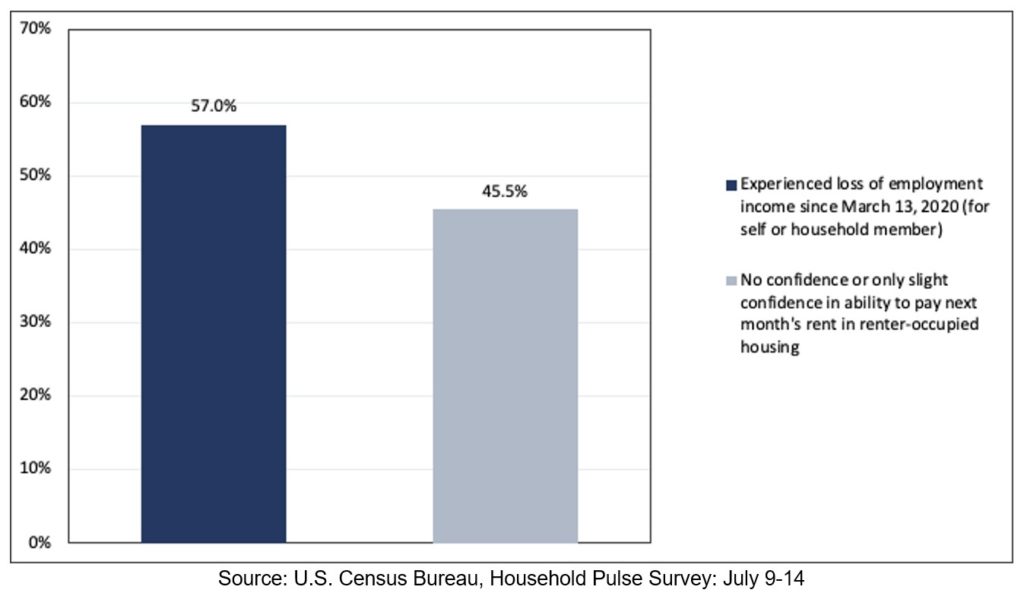

In a U.S. Census Bureau survey taken the week of July 16, 2020, 57% of Black adults reported that someone in their household had experienced a loss of income since March 13, 2020.3 The large group of Black public sector workers is also at risk as states and localities cut their spending to balance their budgets,4 which most state constitutions require.5 As COVID-19 cases rise, many workers who have been able to find jobs may once again find themselves out of work through no fault of their own.

Also, due to a history of mortgage and employment discrimination and other factors that have compounded over time, median wealth for Black households is one-tenth that of white households ($17,600 versus $171,000). Typical white high school dropouts have more wealth than Black college graduates.6 Thus, many Black families of various educational and income lack the resources to address emergencies stemming from the pandemic—like lost income or unanticipated medical bills.7

Income and Housing Insecurity Among Black Adults, July 16-21

To respond to this enduring crisis, the Administration and Congress should reach a bipartisan agreement on a COVID relief package that extends the $600 per week federal supplement to state unemployment insurance for as long as the crisis continues. This support is critical for Black workers who, despite looking for work, have not been able to find employment during the pandemic.

Congress and the Administration should also agree to provide significant fiscal relief to states and localities experiencing revenue losses to prevent layoffs of teachers and other public service workers and to avert harmful budget cuts. Providing direct grants, education funding, and a further increase in federal Medicaid payments to states would provide fiscal relief and help to protect health care during this pandemic.

Finally, the relief package should provide additional assistance through existing programs to help families make ends meet, including increasing SNAP benefits, providing rental assistance to help avert evictions, and expanding income support to workers and families. Any bipartisan agreement should include a temporary extension of the Earned Income Tax Credit for very low-paid workers not raising children and make the Child Tax Credit fully available so that it benefits children from low-income families. These changes would help Black workers in low-paid jobs and children—many of whom are facing harsh circumstances during this crisis and run the risk of long-lasting harm.

The financial support provided by the CARES Act prevented a 33% increase in Black poverty, and this additional relief will be no less significant.8 A stimulus agreement that includes these provisions will provide stability to both individual Black households and the economy more broadly amid the volatility of increasing waves of COVID-19 infections and deaths in many states and localities, and possible state shutdowns or other restrictions that slow economic activity.

This blog post is part of a larger report, Pandemic Relief Priorities for Black Communities, which includes sections on sustaining Black businesses, expanding internet access among Black households, and protecting our democracy.

Endnotes

1 Earl Fitzhugh, Aria Florant, JP Julien, Nick Noel, Duwain Pinder, Shelley Stewart III, Jason Wright, and Samuel Yamoah, COVID-19: Investing Black Lives and Livelihoods (McKinsey & Company, April 2020); Hye Jin Rho, Hayley Brown, and Shawn Fremstad, A Basic Demographic Profile of Workers in Frontline Industries, (Washington, DC: Center for Economic and Policy Research, April 2020).

2 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Table A-2. Employment Status of the Civilian Population by Race, Sex, and Age, (Washington, DC: July 2, 2020).

3 Joint Center analysis of data from U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey: July 9-July 14, (Washington, DC: July 22, 2020).

4 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey: 2019, (Washington, DC: January, 22 2020) (indicating that in 2019 African Americans were 12.3% of the total employed of individuals 16 years of age and older, and 17.5% of the public administration workforce); Steven Pitts, Black Workers and the Public Sector (Berkeley, CA: UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education, April 4, 2011) (“During 2008 – 2010, 21.2% of all Black workers were public employees, compared with 16.3% of non – Black workers. Both before and after the onset of the Great Recession, African Americans were 30% more likely than other workers to be employed in the public sector.”).

5 Wesley Tharpe, “States, Localities Need More Federal Aid to Avert Deepening Budget Crisis,” July 21, 2020, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

6 Tatjana Meschede, Joanna Taylor, Alexis Mann, and Thomas Shapiro, “‘Family Achievements?’: How a College Degree Accumulates Wealth for whites and Not For Blacks,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, First Quarter 2017, 99(1), pp. 121-37; Darrick Hamilton, William Darity Jr, Anne E. Price, Vishnu Sridharan, and Rebecca Tippett, Umbrellas Don’t Make It Rain: Why Studying and Working Hard Isn’t Enough for Black Americans (The New School, Duke Center for Social Equity, Center for Community Economic Development, April 2015) (“Black families whose heads graduated from college have about 33 percent less wealth than white families whose heads dropped out of high school. The poorest white families—those in the bottom quintile of the income distribution— have slightly more wealth than black families in the middle quintiles of the income distribution.”); Michael A. Fletcher, “White High School Dropouts are Wealthier than Black and Hispanic College Graduates,” Washington Post, March 10, 2015.

7 Danyelle Solomon and Darrick Hamilton, “The Coronavirus Pandemic and the Racial Wealth Gap,” March 19, 2020, Center for American Progress.

8 Linda Giannarelli, Laura Wheaton, and Gregory Acs, Initial US Policy Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic’s Economic Effects Is Projected to Blunt the Rise in Annual Poverty (Washington, DC: Urban Institute, July 2020), 13 (“The COVID-19 pandemic response policies reduced poverty for all racial and ethnic groups. For Black non-Hispanic people, the annual poverty rate is estimated to be 15.2 percent with the policies in place, but it would have reached 20.5 percent without them.”).