Tech Policy

Expand Internet Access Among Black Households

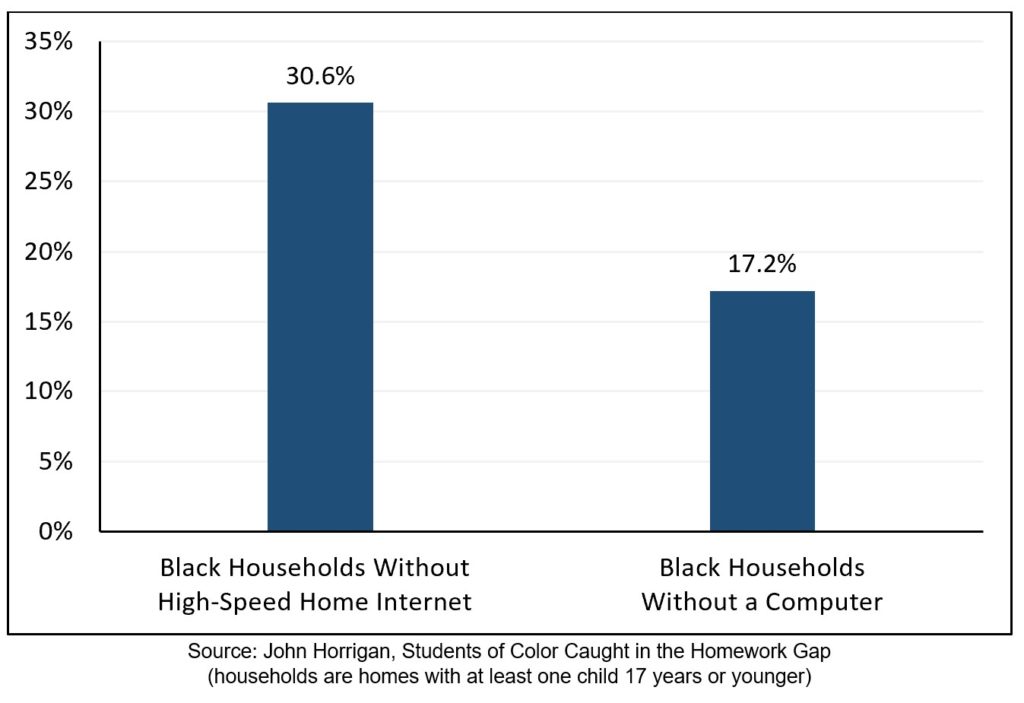

As the pandemic forces many students, workers, and patients to turn to broadband for virtual learning, telework, job applications and interviews, government assistance applications, and medical services, millions of African Americans remain disconnected. In the United States, 34% of Black adults do not have home broadband,1 and 30.6% of Black households with one or more children age 17 or younger lack high-speed home internet (over 3.25 million Black children live in these households).2 While 23% of African Americans are “smartphone-only” internet users,3 mobile subscriptions have more restrictive data caps and pose challenges in completing tasks like homework and job applications.4

Cost is a primary reason many Black families do not have high-speed home internet—both in metropolitan and rural communities.5 The pandemic has placed enormous financial burdens on African Americans, as it has produced the highest Black unemployment rates since 2010 and shuttered the operations of 26 percent of Black business owners.6 Even before the pandemic, three times more households in urban areas remain disconnected than in rural areas,7 and African Americans were already more vulnerable to mobile service being cut off due to expense.8

Congress and the Administration should take simple steps that could immediately expand educational, employment, and health care opportunities for millions of Black children and adults. Specifically, federal policymakers should support a $50 a month emergency broadband subsidy for low-income households or those where a person has experienced a substantial loss of income due to the COVID-19 pandemic.9 This would get families online during the pandemic without being blocked by a credit check or a past overdue internet bill, and would ensure that even those who are struggling financially can afford to stay connected when it counts the most.

The stimulus package should require that the service be of adequate speeds and quality, and also prohibit broadband and phone companies from terminating service, imposing late fees or data caps, or charging customers for going over data caps due to financial challenges stemming from the pandemic.10 Similarly, Congress and the Administration should require that broadband and phone companies provide unlimited data and minutes to users of Lifeline (a federal program that reduces the price of telephone and internet to lower-income Americans).11

Black Households Without High-Speed Internet and a Computer

Over 7.2 million children in the U.S. live in households without a computer—including over 1.84 million Black children.12 The federal relief package should allocate $4 billion for schools and libraries to purchase laptops and tablets, Wi-Fi hotspots, modems, and routers that can be checked out and used at home by students, school staff, and library patrons.13 The stimulus package should also clarify that E-Rate funds can be used to connect students at home who lack broadband because the idea of a “classroom” is now beyond the four walls of a school.

This would be a strong start, but more will need to be done. For example, Wi-Fi hotspots are helpful in the short term, but they are not a long-term solution because they sometimes have data caps and struggle to handle increased usage. Given the likely duration of the economic recovery and the continuing impact on Black workers and businesses, Congress should take additional steps in the future, including the creation of a permanent credit for low-income households and ensuring deployment of broadband access to many areas that lack service (46% of African Americans in the Black Rural South lack home broadband, some due to cost and some due to lack of service).14

This blog post is part of a larger report, Pandemic Relief Priorities for Black Communities, which includes sections on providing financial support for Black workers, sustaining Black businesses, and protecting our democracy.

Endnotes

1 “Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet,” June 12, 2019, Pew Research Center (showing that 21% of white adults, 34% of Black adults, and 39% of Latina/o adults do not have home broadband).

2 John B. Horrigan, Students of Color Caught in the Homework Gap (Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education, July 22, 2020) (showing that of 20.9% of white, 30.6% of Black, and 31.2% of Latino/a households with one or more children age 17 of younger lack high-speed home internet).

3 Andrew Perrin & Erica Turner, “Smartphones help blacks, Hispanics bridge some – but not all – digital gaps with whites,” Aug. 20, 2019, Pew Research Center (“Some 25% of Hispanics and 23% of blacks are ‘smartphone only’ internet users – meaning they lack traditional home broadband service but do own a smartphone. By comparison, 12% of whites fall into this category.”).

4 S. Derek Turner, Digital Denied. The Impact of Systemic Racial Discrimination on Home-Internet Adoption (Washington, DC: Free Press, Dec. 2016) (“Mobile-only households do not have access to the full benefits of fixed broadband connections. Fixed connections typically offer far greater speeds and higher data caps (or no caps). Furthermore, a mobile connection may not always be available to everyone in the household if the primary account holder takes the only mobile device with them when they leave the home.”).

5 While those in the U.S. without high-speed home internet often have multiple reasons for not subscribing, cost of either broadband or devices to access the service are chief reasons. See John B. Horrigan, Measuring the Gap: What’s the Right Approach to Exploring Why Some Americans do not Subscribe to Broadband (Columbus, OH: National Digital Inclusion Alliance, February 2020).

6 Robert Fairlie, The Impact of Covid-19 on Small Business Owners: Continued Losses and the Partial Rebound in May 2020 (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, July 2020), at 6-7, 16 (showing that the decline in the number of active business owners between February and May 2020 was 26% among African Americans, 19% among Latina/os, and 11% among whites).

7 John Horrigan, Digital Divide Policy Enters the National Conversation (Evanston, IL: Benton Institute, August 16, 2019) (“Although a higher share of rural households lacks a home broadband subscription than non-rural ones (by a 21.2% to 15.4% margin), the number of households without a broadband subscription is larger in non-rural areas.”); Angela Siefer and Bill Callahan, Limiting Broadband Investment to “Rural Only” Discriminates Against Black Americans and Other Communities of Color, (Columbus, OH: National Digital Inclusion Alliance, June 2020) (observing that “U.S. households with incomes below $35,000 accounted for 28% of all households, but 60% of those without broadband subscriptions,” and asserting that “cost of service is a major barrier, if not the major barrier, to home broadband access” and that “the U.S. has more than three times as many urban as rural households living without broadband of any kind.”).

8 Andrew Perrin & Erica Turner, “Smartphones help blacks, Hispanics bridge some – but not all – digital gaps with whites,” Aug. 20, 2019, Pew Research Center (“Although smartphones help bridge internet access gaps, other 2014 Pew Research Center data shows that blacks, Hispanics and lower-income smartphone users are about twice as likely as whites to have canceled or cut off service because of the expense.”).

9 HEROES Act, Division M, Title III, Sec. 301 (2020) (Benefit for Broadband Service During Emergency Periods Related to COVID-19.

10 HEROES Act, Division M, Title IV, Sec. 401 (2020) (Continued Connectivity During Emergency Periods Relating to COVID-19).

11 HEROES Act, Division M, Title III, Sec. 302 (2020) (Enhanced Lifeline Benefits During Emergency Periods).

12 John B. Horrigan, Students of Color Caught in the Homework Gap (Washington, DC: Alliance for Excellent Education, July 22, 2020) (indicating that of Black households with one or more children age 17 or younger, 30.6% lack high-speed home internet (a total of 3.3 million Black children) and 17.2% lack a computer).

13 HEROES Act, Division M, Title II, Sec. 201 (2020) (E-Rate Support for Wi-Fi Hotspots, Other Equipment, and Connected Devices); Division B, Title III (appropriates $1.5 billion for laptops and tablets, Wi-Fi hotspots, modems, and routers for schools and libraries as authorized in Division M, Title II, Sec. 201); U.S. Congress, Senate, Emergency Educational Connections Act, S 3690, 116th Cong., 2nd sess., Sec. 2, introduced in Senate May 12, 2020 (appropriates $4 billion for WiFi hotspots, laptops, tablets, modems, and routers for schools and libraries to ensure that all K-12 students have home internet and devices during the pandemic).

14 Mignon Clyburn and Jon Sallet, “Make Broadband Far More Affordable,” Boston Globe, June 27, 2020 (recommending the creation of a permanent program, America’s Broadband Credit, to tackle the affordability crisis). The Joint Center’s analysis of Current Population Survey data found that 46% of African Americans and 28% of whites lacked home broadband in U.S. counties designated as “rural” by the U.S.D.A. with populations over 35% Black (a total of 156 counties which we call the “Black Rural South”).