Protect Our Democracy

Due to COVID-19’s devastating impact on state and local tax revenues, states need resources to implement both accessible vote-by-mail systems and safe in-person voting options. Absent intervention from federal policymakers, the pandemic could diminish Black voter participation and unnecessarily expose those who do vote in person to the virus. Black communities already face disproportionately high rates of infection and death from COVID-19.

The 2020 Wisconsin primary illustrates some of the problems. In Milwaukee City—which is home to 60% of Wisconsin’s Black voters—many poll workers refused to work on Election Day, only 5 of 180 polling places opened, voters waited for hours to vote, and turnout was down by 16,000 voters.1 Total turnout in the precincts with the highest percentage of Black residents dropped 51%.2

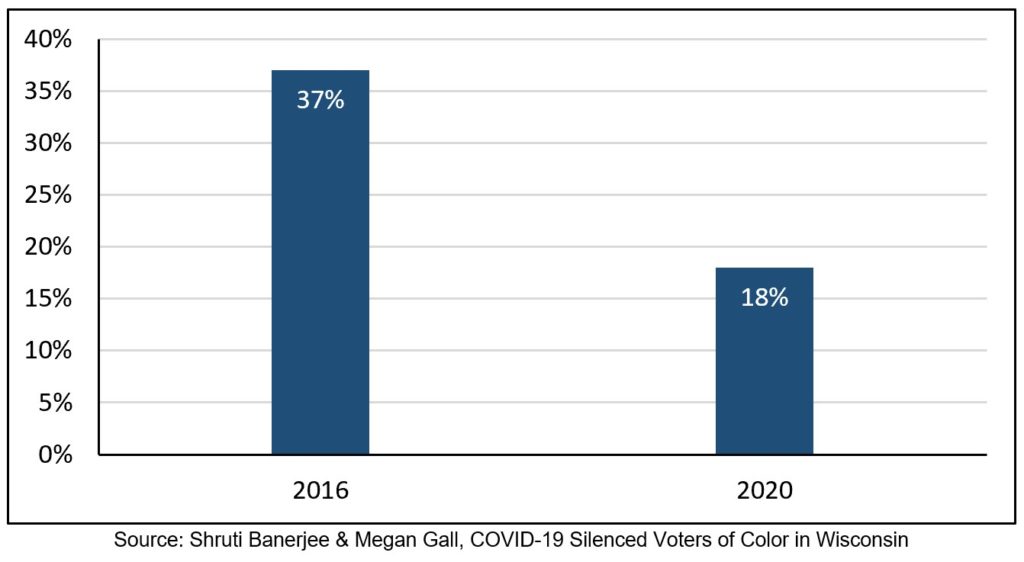

Primary Election Voter Turnout in Milwaukee Precincts with the Highest Share of Black Residents

To address challenges posed by the pandemic, the next stimulus package should provide at least $3.6 billion in funding for states and require that states comply with particular requirements in administering federal elections.3

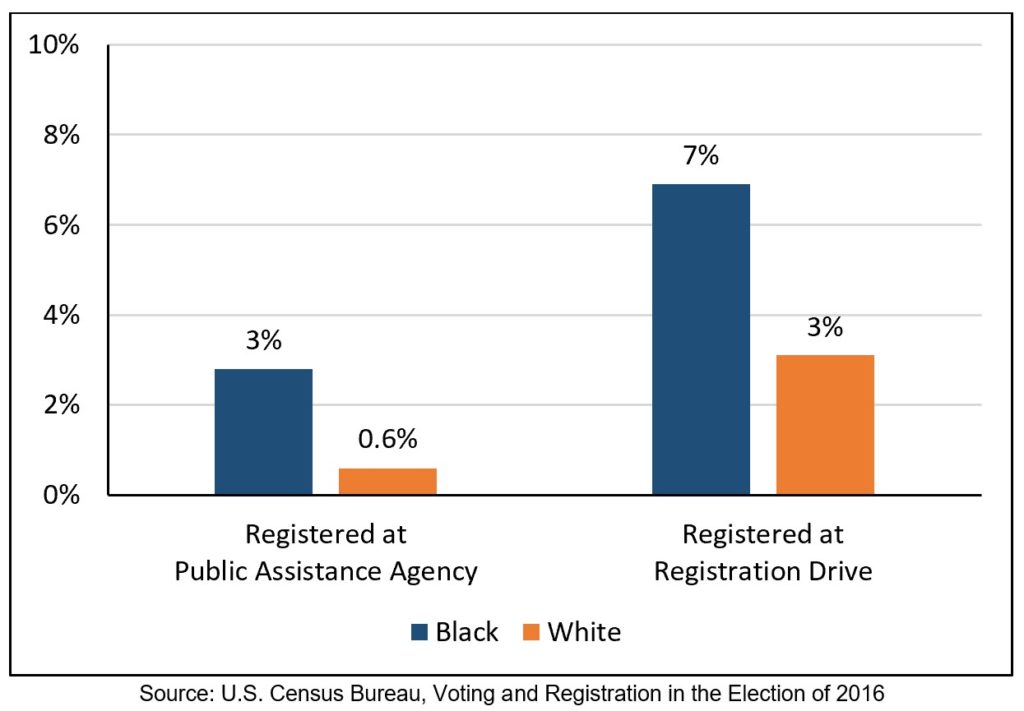

For example, before the virus, Black voters reported being registered through voter registration drives at over twice the rate of white voters, and Black voters registered at public assistance agencies at almost five times the rate of white voters.4 Recognizing that the pandemic has reduced these in-person voter registration opportunities, Congress and the Administration should require that states establish online voter registration systems (already adopted in 82% of states) and same day registration (already adopted in 42% of states).5

2016 Voter Registration Methods

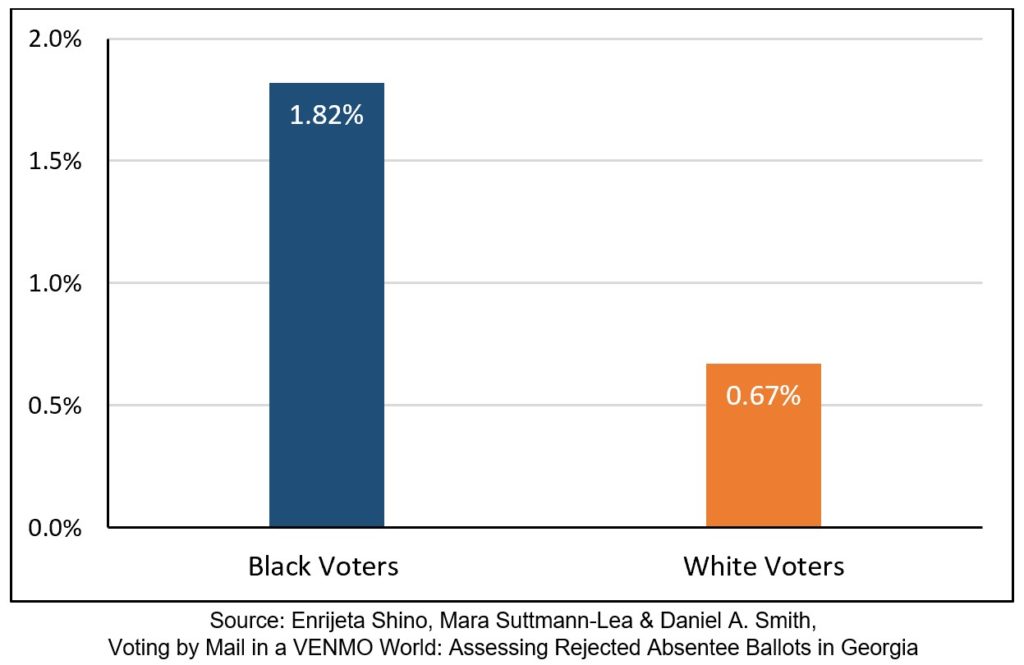

Research suggests that election administrators are about 66%-170% more likely to reject absentee ballots from Black voters than white voters (often through no fault of the voter).6 A study of the 2018 Georgia general election found that “as the percentage of absentee ballots cast by Black voters increases so does the percentage of the rejected ballots cast by” Black voters.7 To address this, the stimulus package should require that voters whose ballots are rejected because election workers perceive a signature discrepancy or due to a missing signature be notified and given 10 days to cure the issue (just under half of absentee ballots rejected in 2016 were invalidated due to a signature discrepancy or missing signature).8

Vote-By-Mail Ballots Received by Election Day Rejected by Officials in 2018 Georgia General Election

The coronavirus relief package should also ensure vote-by-mail is accessible by:

- providing prepaid postage,9

- requiring that ballots be postmarked (rather than received) by Election Day and ensuring the U.S. Postal Service is adequately funded (23% of absentee ballots rejected in 2016 were invalidated because they were “not received on time/missed deadline” (sometimes through no fault of the voter), and limited U.S. Postal resources could cause backlogs with 2020 ballot delivery),10

- allowing voters to return absentee ballots through various methods (e.g., submitting it themselves or designating another person to submit the ballot via mail, at a polling place on Election Day, or at a designated drop-off location), and

- using a signature on the ballot to verify identification (rather than a notarization or a photocopy of an ID card).11

Vote-by-mail is secure, largely due to various safeguards such as mailing ballots to the address on the voter registration rolls, verifying the ballot with a signature matching process, and including a unique bar code on each ballot that is scanned by officials and prevents the voter from casting any other ballot (e.g., like a bar code on a movie ticket).12 One study of vote-by-mail ballots in Colorado, Oregon, and Washington found just 372 possible cases of voter fraud (e.g., double voting or voting on behalf of deceased people) of the 14.6 million votes cast—or one in 39,000 (0.0025%).13 By comparison, a person is 13 times more likely to be struck by lightning at some point in life,14 and 1/39,000th of a 1-mile road is 1.6 inches.

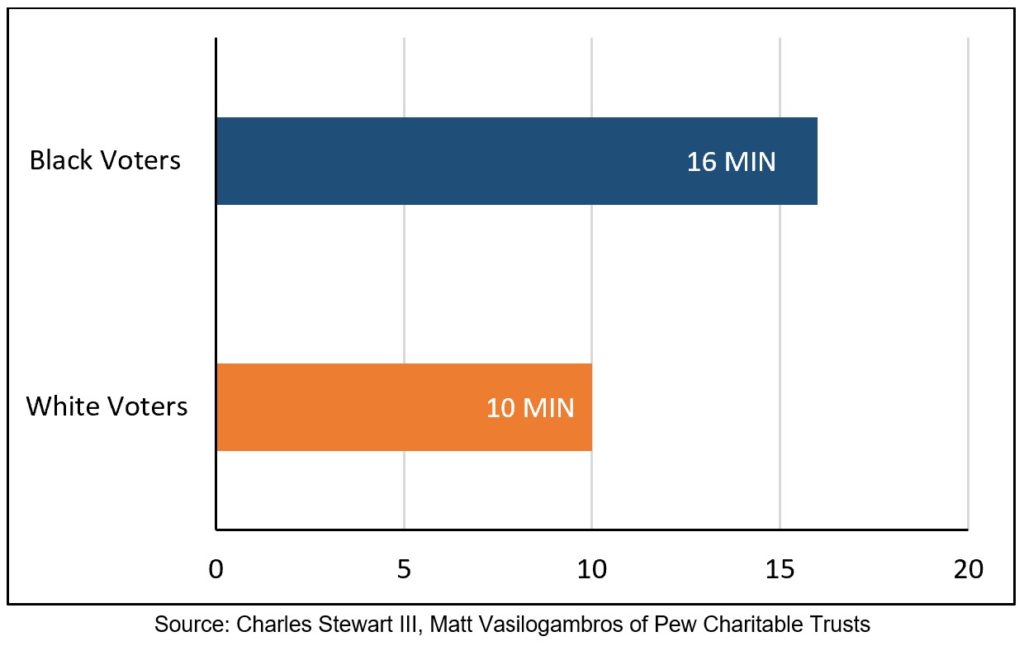

To ensure maximum access to vote, the next stimulus legislation should also require that states provide in-person voting options, and ensure that the in-person options are sanitary, allow for social distancing, and do not have long lines. In November 2016 average African American wait times to vote in person were longer than average white wait times.15 Failing to prevent these disparities in 2020 will not only impose a wait-time tax on Black voters and diminish turnout—long lines will also increase exposure to COVID-19 in Black communities.

Wait Times to Vote in 2016 Presidential Election

To ensure uncrowded in-person voting, the next stimulus package should require that states provide at least 15 days of early in-person voting before Election Day.16 The relief package should require that the Election Assistance Commission impose standards to ensure adequate and nondiscriminatory placement of early and Election Day polling locations,17 and that states develop plans to ensure sufficient staffing and equipment to protect the health and safety of poll workers and voters.18

This blog post is part of a larger report, Pandemic Relief Priorities for Black Communities, which includes sections on providing financial support for Black workers, sustaining Black businesses, and expanding internet access among Black households.

Endnotes

1 Charles Stewart III, “Important Lessons from the Wisconsin primary,” Mischiefs of Faction, April 17, 2020; see also Shruti Banerjee and Megan Gall, “COVID-19 Silenced Voter of Color in Wisconsin,” May 14, 2020, Demos.

2 Shruti Banerjee and Megan Gall, “COVID-19 Silenced Voter of Color in Wisconsin,” May 14, 2020, Demos (noting that in the 3% of Milwaukee precincts with the highest percentage of Black residents, primary election voter turnout dropped from 37% in 2016 down to 18% in 2020).

3 HEROES Act, Division A, Title III (allocating $3.6 billion in election funding); U.S. Congress, Senate, VoteSafe Act of 2020, S 3725, 116th Cong., 2nd sess., introduced in Senate May 13, 2020; U.S. Congress, House, VoteSafe Act of 2020, HR 6807, 116th Cong., 2nd sess., introduced in House May 12, 2020 (authorizing $5 billion and requiring that states provide no-excuse mail-in absentee voting with due process safeguards and at least 20 days of early in-person voting, and authorizing discretionary grant funding for states to support curbside voting, a maximum wait time standard, improved voter registration access, and other election administration matters).

4 U.S. Census Bureau, “Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2016,” May 2017 (Table 12) (those who registered at public assistance agencies included 2.8% of African Americans and 0.6% of white non-Hispanics, and those who registered at a registration drive included 6.9% of African Americans and 3.1% of white non-Hispanics. See also Laura Williamson, “Universally Accessible and Racially Equitable Vote by Mail,” Demos, June 17, 2020.

5 HEROES Act, Division P, Sec. 160007 (Voter Registration) “Online Voter Registration,” National Conference of State Legislatures, July 23, 2020; “Same Day Voter Registration,” June 28, 2019, National Conference of State Legislatures.

6 Daniel A. Smith, Vote-By-Mail Ballots Cast in Florida (Miami, FL: ACLU Florida, September 19, 2018), at 12 (showing that the rejection rate of vote-by-mail ballots by Florida election officials was 66% higher among Black voters than among white voters in November 2012, and 170% higher in November 2016); Enrijeta Shino, Mara Suttmann-Lea, and Daniel A. Smith, “Voting by Mail in a VENMO World: Assessing Rejected Absentee Ballots in Georgia,” University of Florida Liberal Arts and Sciences, May 19, 2020, at 27, Table 1, Panel B (showing that of vote-by-mail ballots received before or on Election Day, 0.67% of white votes were rejected and 1.82% of Black votes were rejected). The research is split on whether African Americans are less likely to vote-by-mail. Some point out that African Americans have relatively high move rates and homelessness rates, and often lack a permanent address. Laura Williamson, How to Build a Racial Inclusive Democracy During COVID-19 and Beyond (New York: Demos, April 2020), at 8 (Vote-by-mail-only elections would be particularly harmful for Black people, who move more frequently than white people,18 and who are disproportionately represented among people experiencing homelessness); Daniel A. Smith, Vote-By-Mail Ballots Cast in Florida (Miami, FL: ACLU Florida, September 19, 2018), at 12-13 (showing that in Florida the percentage white voters were 62% more likely than Black voters to vote-by-mail in November 2012, and 51% more likely to vote-by-mail in November 2016). On the other hand, MIT professor Charles Stewart found did not find statistically significant differences among Black and white voters in three types of vote-by-mail states (those that require an excuse for an absentee ballot, those that do not require and excuse for an absentee ballot, and those that universally vote by mail), but found that white voters were about 7 points more likely to vote by mail in states that allow voters to request that they be permanently added to the list for absentee voting so that the voter automatically receives an absentee ballot for all elections (about 15 states). Charles Stewart III, “Some Demographics on Voting by Mail,” Election Updates, March 20, 2020.

7 Enrijeta Shino, Mara Suttmann-Lea, and Daniel A. Smith, “Voting by Mail in a VENMO World: Assessing Rejected Absentee Ballots in Georgia,” University of Florida Liberal Arts and Sciences, May 19, 2020, at 14.

8 HEROES Act, Division P, Sec. 160003 (2020) (Early Voting and Voting by Mail). See also Election Assistance Commission, The Election Administration and Voting Survey: 2016 Comprehensive Report, (Silver Spring, MD, 2017), at 11 (indicating that of absentee ballots rejected, 27.5% were rejected due to “non-matching signature” and 20% were rejected due to no voter signature).

9 HEROES Act, Division P, Sec. 160005 (2020) (Early Voting and Voting by Mail).

10 HEROES Act, Division A, Title III, (2020) (Financial Services and General Government–allocating an additional $25 billion for the U.S. Postal Service) and Division P, Sec. 160003 (2020) (Early Voting and Voting by Mail). Election Assistance Commission, The Election Administration and Voting Survey: 2016 Comprehensive Report, (Silver Spring, MD, 2017), at 11 (detailing reasons absentee ballots were rejected); Pam Fessler and Elena Moore, “Signed, Sealed, Undelivered: Thousands of Mail-In Ballots Rejected for Tardiness,” July 13, 2020, NPR (in the 2020 primaries “at least 65,000 absentee or mail-in ballots have been rejected because they arrived past the deadline, often through no fault of the voter”); Michelle Ye Hee Lee and Jacob Bogage, “Postal Service Backlog Sparks Worries that Ballot Delivery Could Be Delayed in November,” Washington Post, July 30, 2020 (the “U.S. Postal Service is experiencing days-long backlogs of mail across the country after a top Trump donor running the agency put in place new procedures described as cost-cutting efforts, alarming postal workers who warn that the policies could undermine their ability to deliver ballots on time for the November election.”).

11 HEROES Act, Division P, Sec. 160003 (2020) (Early Voting and Voting by Mail).

12 Elise Viebeck, “Minuscule number of potentially fraudulent ballots in states with universal mail voting undercuts Trump claims about election risks,” Washington Post, June 8, 2020; Mike Baker, “The Facts About Mail-In Voting and Voter Fraud,” NY Times, June 22, 2020.

13 Elise Viebeck, “Minuscule number of potentially fraudulent ballots in states with universal mail voting undercuts Trump claims about election risks,” Washington Post, June 8, 2020 (“But a Washington Post analysis of data collected by three vote-by-mail states with help from the nonprofit Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC) found that officials identified just 372 possible cases of double voting or voting on behalf of deceased people out of about 14.6 million votes cast by mail in the 2016 and 2018 general elections, or 0.0025 percent”).

14 “Flash Facts About Lightning,” June 24, 2005, National Geographic (“The odds of being struck in your lifetime is 1 in 3,000).

15 Matt Vasilogambros, “Voting Lines Are Shorter—But Mostly for white,” February 15, 2018, Pew Charitable Trusts (sample indicating that white voters waited 10 minutes and African Americans waited 16 minutes); M. Keith Chen, Kareem Haggag, Delvin G. Pope, Ryne Rohla, “Racial Disparities in Voting Wait Times: Evidence from Smartphone Data,” arXiv:1909.00024, August 30, 2019 (an analysis of cell phone data showing that voters in November 2016 predominantly Black neighborhoods waited 29 percent longer on average than voters in predominantly white neighborhoods, and were 74% more likely to spend more than 30 minutes at their polling place).

16 HEROES Act, Division P, Sec. 160003 (2020) (Early Voting and Voting by Mail) (requiring at least 15 days of early in-person voting; VoteSafe Act, Sec. 3, (d) (2020) (requiring at least 20 days of early in-person voting).

17 HEROES Act, Division P, Sec. 160003 (2020) (Early Voting and Voting by Mail).

18 HEROES Act, Division P, Sec. 160002 (2020) (Requirements for Federal Election Contingency Plans in Response to Natural Disasters and Emergencies). See also “Considerations for Election Polling Locations and Voters: Interim Guidance to Prevent Spread of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19),” June 22, 2020, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Election Assistance Commission (providing best practices to ensure safe and sanitary in-person voting, including PPE for poll workers, regular sanitizing of equipment and machinery, masks, minimal lines and crowds, adequate ventilation, special voting hours reserved for at-risk populations, and larger rooms and a setup that allows for social distancing.).